Scientists from the Fraunhofer Institute for Electronic Nano Systems (ENAS) are working on the tiny component, weighing just one gramme, with the aim of mass producing the chip for about €1 using conventional technologies.

“This will allow it to be integrated in smartphones, for instance,” explained Dr Alexander Weiss, head of department for multi device integration at Fraunhofer ENAS.

A question of size

At present, spectrometers – which can also be used for other applications such as testing air quality and detecting pollutants in water – weigh several kilogrammes and cost thousands of pounds to produce.

Although handheld versions weighing less than that do exist, they are still unsuitable for mass market adoption due to cost, production methods and operation. They can often have limited functionality and require two hands, one for the detection device and the other to hold the smartphone to which the resulting data is relayed.

Just like conventional spectrometers, the mini version developed at Fraunhofer ENAS works by emitting light beams in the infrared range. The light of different wavelengths is then fragmented using a tuneable filter and conducted to a detector by means of integrated waveguides.

The amount of light reaching the detector at specific wavelengths produces a spectrum that can be analysed to provide the reading.

While conventional spectrometers usually consist of discrete components, the team at Fraunhofer ENAS have created the smaller version by integrating the beam guidance, splitting of the individual wavelengths and detection function in one plane. “We are therefore also calling this an in-plane spectrometer,” Weiss said.

Smart learning

As well as miniature size, integration into smartphones requires operation of the spectrometer to be easy and intuitive, with the ability to provide the user with clear evaluations.

The researchers, therefore, have developed smart learning algorithms. “If many people use the technology, the system will learn quickly,” Weiss explained.

Operation via smartphone will require the use of a special app, with instructions to guide the user through the measurement process. The software will also compare the spectrum generated with reference spectra entered in a database by specialists beforehand.

Further testing

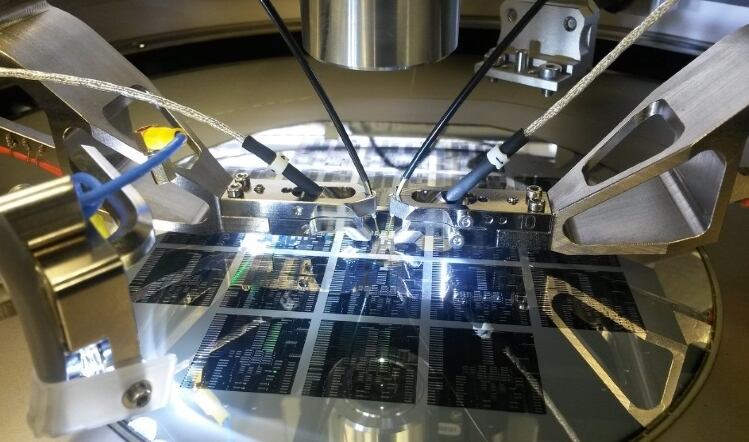

The researchers at Fraunhofer ENAS have already produced the spectrometer chips and provided proof of concept. They are now making assessments regarding the movement of the individual components and the transmission of light coupled into the waveguide.

If the research goes as planned, the spectrometer could find its way to the mass market in around two years’ time, according to the team.

“We designed the spectrometer in a way that would allow it to be mass-produced inexpensively using conventional microsystems engineering technologies," Weiss said. “Manufacturers can use the processes that are standard on the large fabrication lines.”