Much has been made of the shift away from carbonated, high-sugar beverages, towards milk and milk-based alternatives. But, for now at least, it doesn’t appear to be seismic.

Take ready-to-drink (RTD) tea, often considered a healthier option than other soft drinks. While Euromonitor refers to “solid growth” in volume and value terms during 2017, it also notes that overall per capita consumption remains low. At the same time, it says, Britvic-owned market leader Lipton lost 21% of its RTD tea market share in the four years to 2017.

“In the UK, RTD teas have been predominantly represented by iced tea,” says Colm O’Gorman, development programme manager at GEA Group. “And making an iced tea is somewhat similar to making many other types of soft drink.”

That doesn’t mean, however, that change won’t happen. With the advent of the Soft Drinks Industry Levy in April, manufacturers have more incentive than ever to move away from traditional formats and explore new product development (NPD) avenues. And for those willing to invest in the right drink – and the right processing kit – the opportunity is clear.

Asian markets have led the way when it comes to milk teas, tea infusions and kombucha (fermented tea), as well as combinations of fruit and other ingredients. O’Gorman anticipates the UK will follow with similar trends.

‘Wider health and wellness trends’

“The consumer tends to identify with the freshness of the product, as part of wider health and wellness trends – and if the tea is made directly from the leaves, it has that market positioning and higher value,” he says. “This means bigger challenges, but also huge opportunities.”

GEA can supply aseptic process, filling and hot-fill lines, but O’Gorman talks about “complete end-to-end solutions” for teas, from dry raw materials handling through to the increasingly important element of waste handling, with its high moisture content. The use of centrifuge clarifiers is another of the key process stages in RTD tea production.

“We offer automated processes, with all the opportunities associated with digitisation, including tighter process control and good repeatability,” says O’Gorman.

Whether derived from oats, nuts or soya, plant-based dairy alternatives represent another growth area for GEA and other process suppliers.

“We’re talking about aseptic processing, separation rather than clarification, using a centrifuge decanter, and we have enzymation steps, too,” he says. “There are more stages involved than with RTD teas, for example.”

Dutch-based JBT Food & Dairy Systems has historically specialised in the fresh milk sector, but its European sales manager Klaas Kummeling believes the urge to move beyond more commoditised products is a strong one.

“Globally, we see more of our customers exploring higher-margin products,” he says. “Here, for beverages, Asia tends to be ahead of the market, but Europe seems to be following the same trend.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by Bram Bergsma, product line operations manager at JBT. “We have a lot of European customers that are already big in soya milk, for example,” he says. “In Spain, there are some very big producers making these higher-margin products.”

Stand the test of time

Of course, determining what products – and process features – are going to stand the test of time is an art in itself. “Europeans in particular are aware that a product may be popular only for a very short time,” says Kummeling.

“Generally, if they can earn back the cost of their investment within two years, they’re willing to invest. If payback is longer than two years, it’s less likely.”

Even within fresh milk, there are signs of a move away from a market dominated by larger dairies handling huge volumes. “We’ve run pilot projects for smaller operators – in France for example – that wanted to follow their own independent approach with retailers,” says Bergsma. This can be seen as part of the consumer desire to ‘buy local’ – a trend also seized upon by some major retailers.

While the daily output of a major European dairy is likely to be close to a million litres, JBT’s SteriCompact is tailored toward smaller operators in the lower volume market.

Suitable for ultra-high temperature (UHT) products processed in a capacity range of up to 4,000 litres per hour, the SteriCompact uses the same design of concentric, helical tubes for heat treatment as JBT’s SteriDeal HX UHT system.

The base process, designed for standard dairy applications, can be combined with optional modules for products such as juices, soya products or extended-shelf-life milk.

Non-dairy alternatives

It’s important to consider that, however subtle, there are differences in the way low-acid non-dairy alternatives behave in processing compared to milk.

“The challenges are similar, as well as typical running times and temperature profiles,” says Maria Norlin, juice, nectars and still drinks sub-category manager at Tetra Pak. “But, because we are talking about different proteins, their behaviour is similar, but not completely the same.”

As well as providing equipment for less familiar product areas, Tetra Pak says a lot of effort goes into optimising processing in more established categories.

As a part of this approach, it offers what it calls Intelligent Customisation. This involves assessing the specifics of the customer’s running times, utility costs, target quality, and other variables.

“If you wanted to make your high-acid process more efficient, for example, you might be able to move from a batch system to inline blending,” says Norlin. “From around 5,000 litres an hour capacity, inline blending can be suitable. Benefits include the space saving on tanks.”

In terms of optimising the process further, the customer can also often lower the second-stage pasteurising temperature of products such as orange juice to around 80°C, Norlin says. “This will be more energy-efficient and can also improve product quality.”

Clean-in-place (CIP) is another area where savings can often be found. Depending on the precise product profile, there may be more or less fouling in the processing equipment, explains Norlin. “Customers can often optimise their CIP, making a time saving of up to 50% and, clearly, cost savings as well.”

New HPP markets emerge

Fuelled by consumer concerns over the effect of heat treatment on products and their nutrient content, high-pressure processing (HPP) continues to make inroads into beverage markets, especially juices and smoothies, but also newer categories such as cold-brewed coffee and probiotic drinks.

The technology used to be applied only to pre-bottled beverages, but that changed in September with the launch of the first Hiperbaric Bulk system for processing beverages pre-fill. It could revolutionise the way that larger fillers in particular view the technology.

There are huge shelf-life advantages of using HPP, claims Lisa Wessels, chief marketing officer at US equipment firm JBT-Avure. “With fresh orange juice, product life may be up to two weeks or so, but with HPP, you can achieve a four-month shelf-life,” she says.

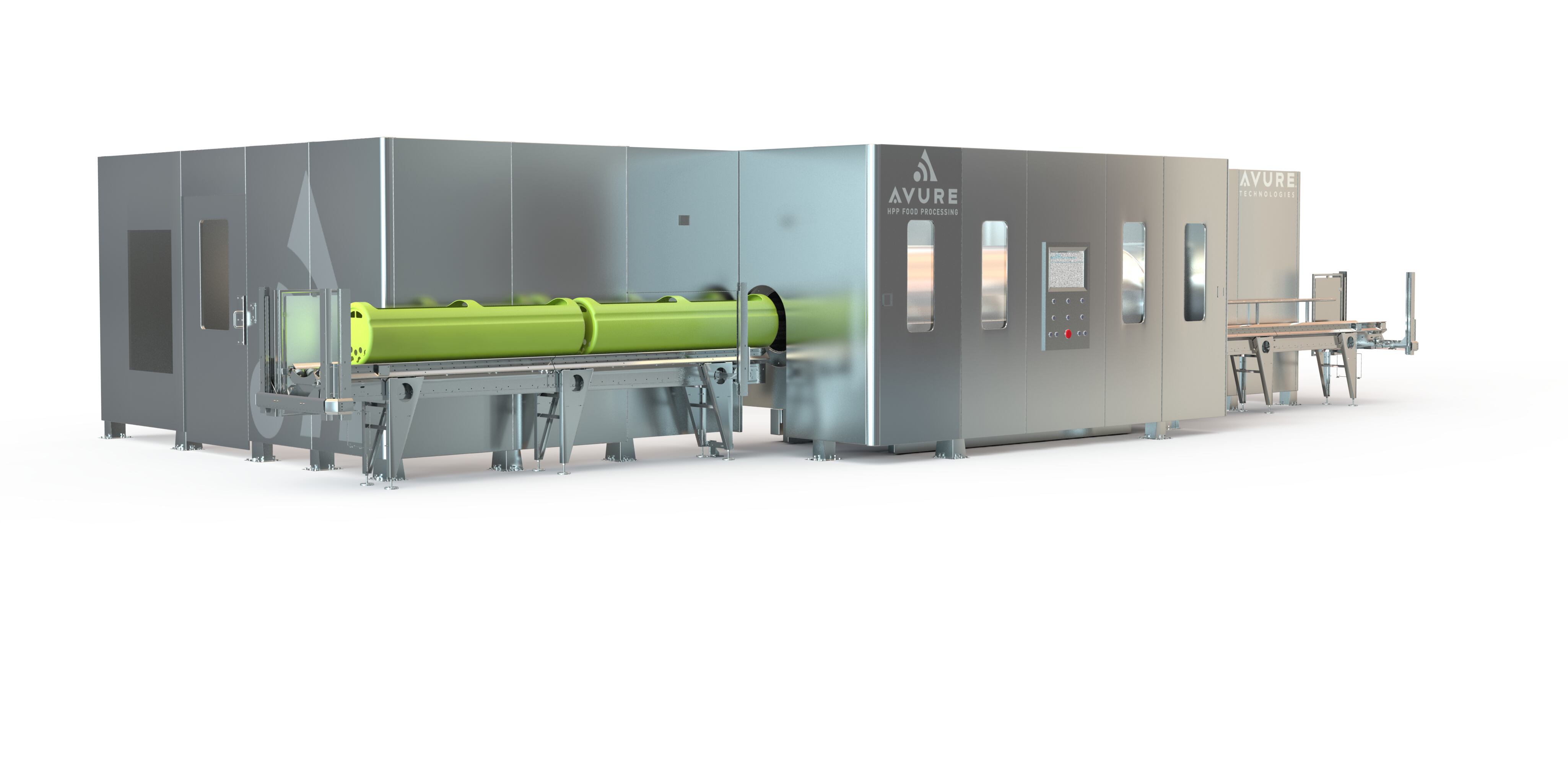

While development work with HPP goes back some 30 years, commercialised systems have only been available for the past 10 to 15 years. Recent changes have not altered the fundamental technology, says JBT-Avure, but have focused on machine capacity.

“Just five to eight years ago, the largest machines were 300 litres [water volume],” says Wessels. “But today, we have a 525-litre system [see above].”

In fact, Hiperbaric says its Bulk system uses two 525-litre vessels in parallel to process up to 10,000 litres an hour.

Anything that brings down the costs associated with HPP has to be welcome, though Wessels argues that there are already hidden cost savings thanks to the increased capacity per cycle and the reduction in product wastage due to a longer shelf-life.