Last week saw news Oatly lose a long-term battle against Dairy UK.

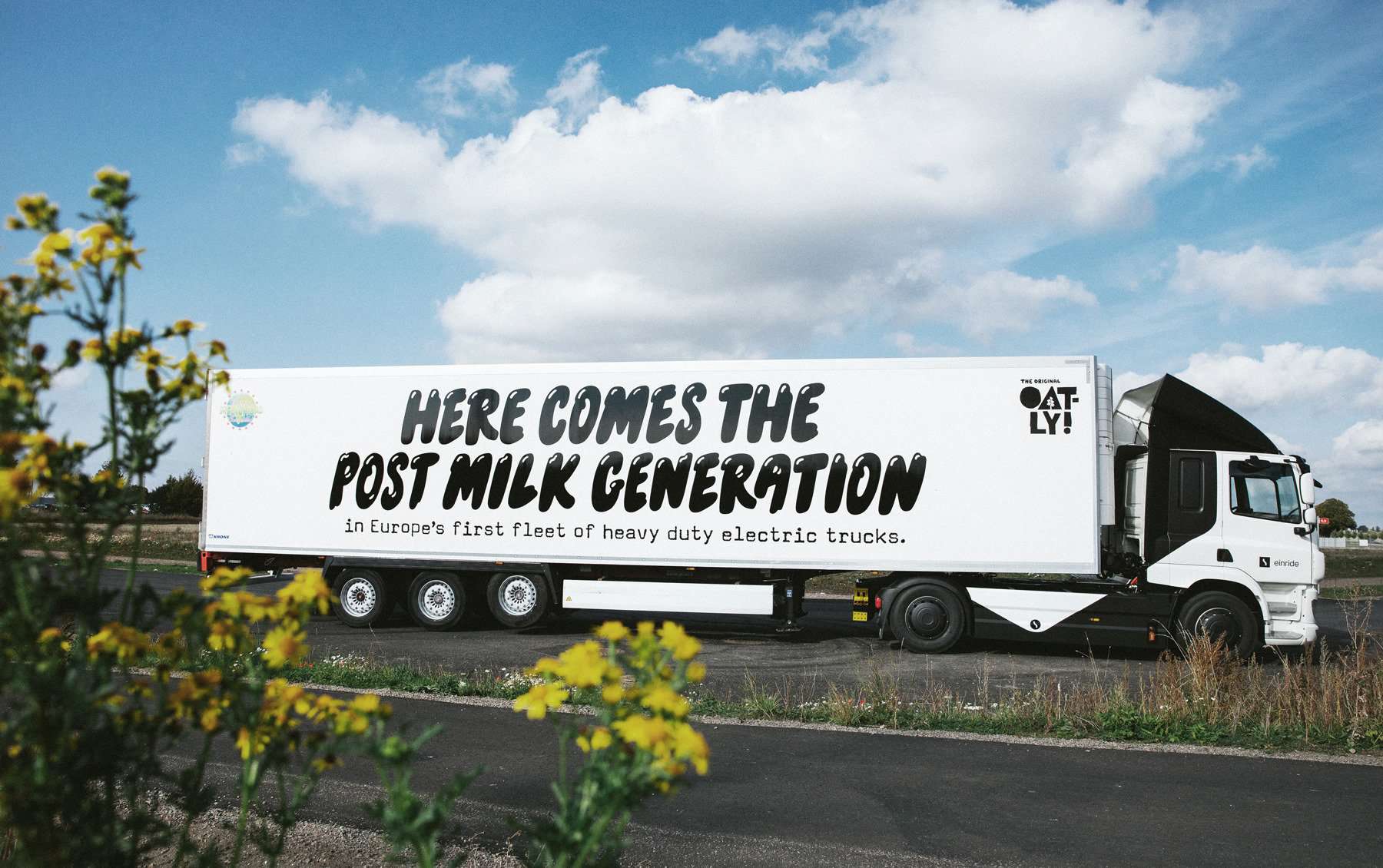

The debate centred on the oat-based dairy alternatives’ UK trade mark registration for the slogan ‘POST MILK GENERATION’, covering oat‑based food and drink products as well as T‑shirts.

Dairy UK, the trade association for the UK dairy industry, sought to invalidate the registration, arguing that the EU‑derived Regulation (which are still applied in the UK) strictly regulates the use of protected dairy terms.

The Regulation prohibits the use of ‘milk’ or ‘milk products’ for non‑dairy goods unless a narrow exception applies. Although Oatly challenged the decision all the way to the Supreme Court (the UK’s highest court), the appeal was unanimously dismissed. This confirmed Dairy UK’s position that Oatly’s slogan could not remain registered for oat‑based food and drink products.

The Supreme Court held that under the Regulation, a ‘designation’ covers any use of a protected dairy term ‘in relation to’ a food or drink product. It is therefore irrelevant that POST MILK GENERATION was not being used as actual name of Oatly’s products; the presence of the word ‘milk’ within the slogan was enough to make it a prohibited designation when used for plant‑based goods.

As a result, the decision captures not just product naming but all forms of marketing, including packaging, advertising, digital content and social media. Essentially if a dairy term appears anywhere in connection with the product, there is a risk of falling foul of the regulation.

However, because the dairy‑term rules apply only to food products, Oatly was allowed to keep its UK trade mark registration registered for T‑shirts, where no such restriction applies.

This decision sets an important precedent for plant-based producers going forwards and raises some interesting points to consider when it comes to branding and marketing materials.

What’s the impact of this decision on plant-based producers?

The decision has significant implications for one of the UK’s fastest‑growing food sectors. Plant‑based producers must now exercise particular caution when using dairy‑related terms, even creatively or indirectly, in slogans or wider brand communications.

Oatly’s slogan was not a product descriptor but a slogan, yet the court still found it to be an unlawful use of the protected term ‘milk’.

Even if plant-based producers are using ‘milk’ as part of a fun and creative slogan such as ‘beyond milk’ or ‘breaking up with milk’ etc., it can still fall foul of the rules and so rephrasing would be sensible.

What can plant-based brand owners use instead?

Terms such as ‘milk‑free’, ‘non‑dairy’, or ‘dairy‑alternative’ may be allowed, as they are clear descriptors and directly communicate a characteristic quality, but such use must be totally unambiguous.

What about other milk alternatives like soy milk and almond milk?

In this case, it did not matter that terms like ‘oat milk’, ‘soy milk’ and ‘almond milk’ are frequently used by consumers in everyday language, the court made clear in the judgement that their focus lay on upholding fair competition, not on everyday consumer usage.

Producers themselves are therefore restricted from using these terms, even where there is no risk of deception. This presents a real communication challenge for brands trying to describe their products in a way customers readily understand.

What about meat‑free alternatives?

At present, meat‑related terms such as ‘burger’, ‘steak’ and ‘sausage’ remain permissible for plant‑based products. However, the EU is actively progressing towards reserving some meat designations as well.

Recent legislative proposals would introduce protected meat designations, similar to dairy rules and so it is entirely possible that similar restrictions may be introduced in the future in the EU and potentially mirrored in the UK.

Key takeaways

The court’s decision was expected, but it sets a high bar for any plant-based producers using dairy-related language. Other plant‑based producers using similar language could face challenges following this decision.

Ultimately this case serves as a reminder to producers of plant-based products (or any products) to seek early legal advice relating to new brand names and slogans to avoid the risk of legal action and costly rebranding. If using such terms in any marketing currently, now is a good time to review existing branding and marketing to ensure compliance.

In short, if plant-based owners are to take away anything from this case, it is this: unless the wording is strictly and explicitly descriptive, using dairy‑related terms in plant‑based marketing is now a high‑risk strategy.

About the author

Anousha Davies is an associate and chartered trade mark attorney in the intellectual property team at Birketts LLP.