More than two-thirds of the country are failing to hit a health baseline - but why? Is it diet, lifestyle or education? Or, more than likely, it is a combination of three forming a deadly trifecta.

Despite a series of relatively drastic government measures over the past decade, the rate of overweight adults has continued to increase at a worryingly steady pace.

Obesity-related health issues now cost an already creaking NHS around £6.5 billion a year, according to the Department of Health and Social care; an eye-watering sum that is predicted to rise to close to £10 billion by 2050.

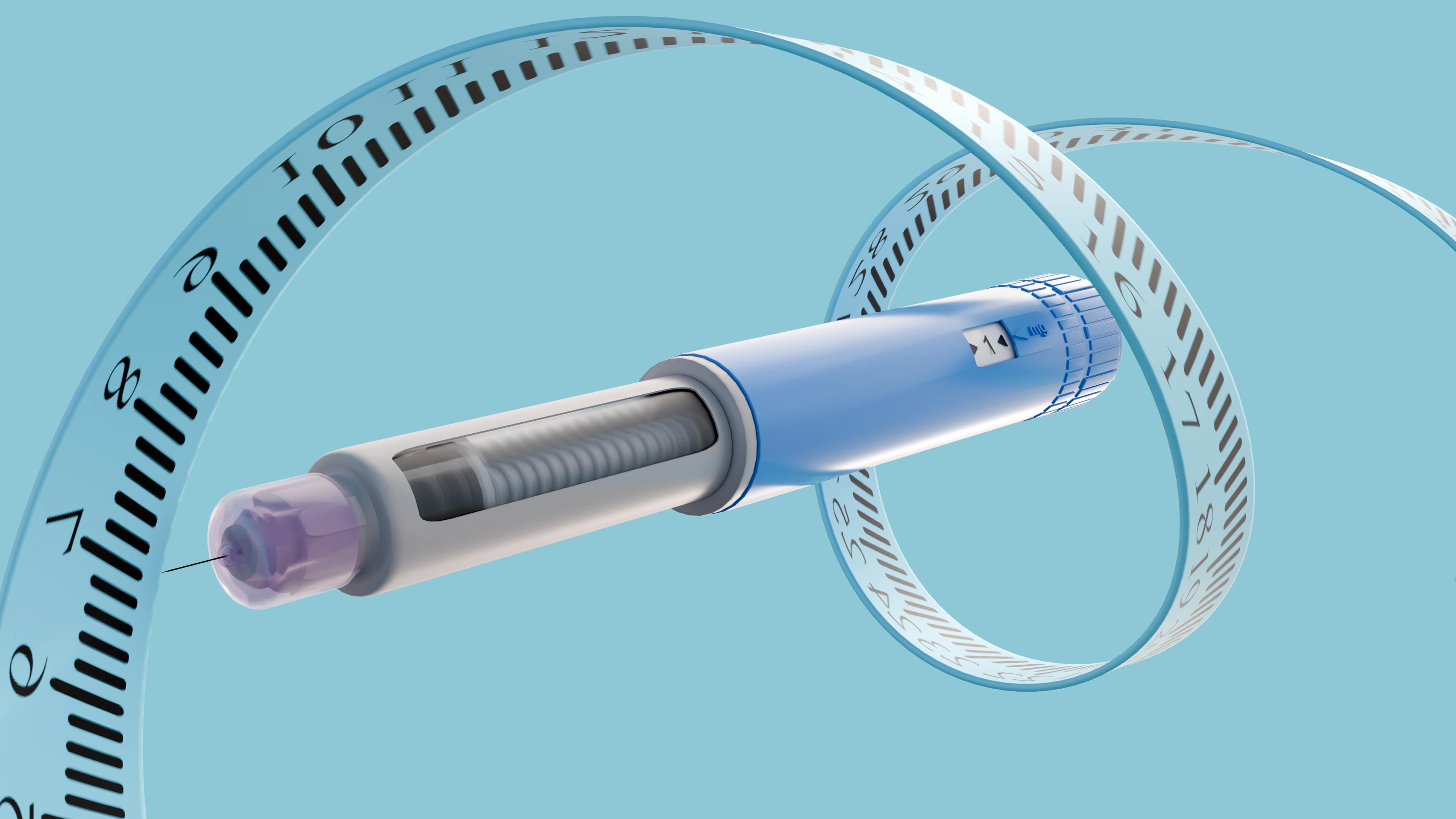

The emergence of GLP-1 medications such as Ozempic could prove to be a game changer for the future of obesity throughout the Western Hemisphere – but prevention should still be the goal, and both individuals and food manufactures are culpable for the situation we now find ourselves in.

Obesity crisis: How has it come to this?

While the bulk of the damage appears to have been done in the final 20 years of the last century, when the obesity rate trebled from 1980 to 2000, the problem is still growing despite concerted efforts to get the numbers under control.

But how did we get here? After all, the obesity rate was still only hovering around 13% in 1990 – and while we can obviously point to a decline in manual labour jobs and the development of an increasingly educated workforce that has a preference for sedentary office jobs – the make-up of our food has also changed dramatically.

Since the advent of mass industrial manufacturing, our food has become more calorie dense – providing us with more energy than we will ever be able to use up in our modern lifestyles, as dietician Dr Carrie Ruxton explained: “The ‘energy in, energy out’ equation is critical. It’s fashionable to claim that obesity isn’t about calories and instead blame food processing, carbohydrates, stress or advertising etc., but this is false.

“These factors are enablers but they aren’t the root cause. Since the 1960s, there has been a significant reduction in manual labour, walking and active leisure and an increase in food energy density (calories per serving), food availability and affordability (food prices relative to wages).

“This has resulted in people consistently eating more than they need. The fear of giving offence to people with excess body fat has compounded the problem as teachers, healthcare professionals and workplaces are now reluctant to intervene to help people lose weight”.

Largely echoing Ruxton’s opinion, dietitian and founder of Chickpea Marketing Corrine Toyn also pointed to growing levels of food poverty across the UK as another key driver of obesity: “The UK hasn’t arrived at an obesity epidemic by accident — it’s the product of an environment that makes unhealthy choices the easiest choices.

“Less expensive, high fat, sugar and salt food is heavily marketed and often more accessible and signposted to than fresh alternatives. Combine that with increasingly sedentary lifestyles and widening health inequality, and it’s no surprise obesity has risen.”

Too little, too late?

While growth of UK citizens classified as overweight or obese has slow - only growing by around 4-5% since the start of the century - we are yet to see a decline in numbers.

Government parties have made attempts to incite change over the years, but between the non-mandatory measures and U-turns, successes has been far and few between.

The total online ban on junk food advertising and the pre-watershed TV ban should hopefully help at some point down the line, limiting children and young peoples’ exposure to positive depictions of HFSS foods.

While the Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL) or so-called ‘sugar tax’ introduced in 2018 has already forced manufacturers to re-think the content of their drinks – reformulating them into much healthier recipes.

More changes have been proposed too, including modifications to the Nutrient Profiling Model (NPM) and the expansion of the sugar levy - the so-called milkshake tax. These have had mixed reviews, with many industry stakeholders claiming tweaks are unfair and nonsensical.

If anything, it is surely tangible measures like these, combined with better food education that will stand the best chance of having an effect – but Toyn isn’t convinced.

“Policies like the sugar tax and HFSS ad bans are a good start, but they’re not a silver bullet. They can nudge industry in the right direction, but obesity is far too entrenched for quick fixes,” she elaborated.

“The new Nutrient Profiling Model could strengthen accountability, yet the real test is whether government is willing to tackle the deeper drivers — poverty, food access, and the constant marketing of unhealthy products. Without sustained action, these measures may help, but they won’t be transformative.”

Ruxton also believes the Government’s approach to be inadequate, and is strongly critical of the high street’s impact on the issue: “All successive governments have done is put pressure on the food industry to reformulate salt and sugar, with the result that overall calories remain unchanged. Taking out sugar and putting back other types of carbohydrates, fat or protein is ineffective. We need reductions in energy density, portion sizes and availability of discretionary foods.

“The government has ducked the issue on physical activity in schools, creating exercise opportunities for adults, boosting NHS or occupational weight management services and limiting the availability of out of home snacking. Our toxic environment is now so out of control that it’s impossible to walk 100 metres down a typical high street without encountering shops selling cakes, sweets, takeaways, vapes or fizzy drinks.”

A new dawn?

With the likes of Ozempic and Wegovy gaining more traction, we stand on a precipice of sorts – and while it’s still very early days, it’ll be fascinating to see what impact these products have on obesity rates across the world.

With some estimates suggesting that as many as 7% of UK adults have used GLP-1s, these drugs are only set to grow in popularity as they become available in new, cheaper formats.

Still, even now with these drugs marked up at a costly price, data shows the gap between the most and least deprived is unexpectantly narrow.

This gap was referenced in a post from former government health tsar, Henry Dimbleby, on Linked In, as he cited a graph published in The Times.

“The gap between the poorest and richest deciles is surprisingly narrow. This tells you how strong the pull of these drugs is - and what people are willing to give up to get them,” he wrote.

We are already starting to see how these medications are impacting NPD, with a slew of products released in recent months specifically to accompany people with reduced appetites.

But Toyn is urging caution, calling for a educational approach over a blanket roll-out of such drugs.

“The rise of GLP-1 drugs marks a real cultural turning point — obesity is increasingly being understood as a medical issue that requires medical treatment. Supermarkets jumping on the ‘GLP-1-friendly’ trend could help consumers make healthier choices, but it also raises questions about commercial opportunism," she said.

“My view is that these ranges may support individuals in a positive way, but they won’t solve obesity on their own. Education on how to sustainably achieve a healthy balanced diet and lifestyle is needed. Long-term progress still depends on fixing the food environment, not just relabelling it for commercial appeal.”

Citing widespread usage of GLP-1s as the result of a growing public frustration over elusive weight loss services, Ruxton spotlighted the importance of further human trials before mass take-up: “The public have quite rightly become frustrated with a lack of access to weight management services and are taking matters into their own hands. However, I would caution supermarkets and manufacturers jumping on the GLP-1 band wagon without commissioning scientific research into the effectiveness of their new products.

“Having looked at the literature myself, it is still unclear which nutrients and food ingredients help people to manage their appetite. Animal and cell studies suggest that whey protein, leucine, long-chain fatty acids, fermentable fibres, green tea polyphenols and butyrate may offer benefits, but human trials are now needed to establish dose and efficacy”.

It remains to be seen what tangible impact weight loss medication and the Government’s anti-obesity measures will have on the issue, but coupled with these new drugs, it’s not impossible to imagine obesity rates falling in the next few years.